Excerpt from Hugging My Father’s Ghost, released in 2024 by Spuyten Duyvil Publishing

My mother, Mildred “Mickey” Rogow, was a complicated soul. Brilliant, beautiful, funny, the life of the party, she could also be sharply critical. Her moods were highly changeable, even erratic.

Born in 1919, my mom spent her early childhood on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the 1920s, then the most densely populated slum in the United States. Families squeezed into railroad flats with little ventilation or light, and the rooms became active workplaces during the day.

My mother’s father, my Grandpa Saul, was not much of a breadwinner. He often owed back rent, so several times the family had to pack up what belongings they could carry in the middle of the night, and sneak out in the dark to a new apartment in a different neighborhood. My mother had to change neighborhoods from the Lower East Side, to Harlem, to the South Bronx, one step ahead of the last landlord. Her shame at having to move under cover of night as a child was something she talked about her whole life.

My mother was a beauty with wavy dark hair, long legs, and hazel eyes.

Mickey, 1948

In her teens, during the worst years of the Great Depression, she had to scramble to find work. Her first job was as a “Chiclet girl,” giving out chewing gum samples while exclaiming, “Chew Chiclets and cheer up!”

A Chiclet girl giving out a sample

Strangely, this was actually a dangerous job. My mom, Mickey, would be driven by a salesman to a poor, crowded New York neighborhood on a hot summer day where the local kids mobbed her, all reaching to grab samples. She wore a heavy velvet outfit, stifling in the heat, and she carried a tray suspended from a strap around her neck, so when the kids snatched the samples, she was in danger of getting the strap twisted around her throat.

Mickey had an ingenious solution. When she and the salesman drove up to a local candy store to give out samples, Mickey immediately picked out the biggest, toughest kid, and offered the local bruiser half the gum in exchange for getting all the other kids to form an orderly line.

Her next job was safer, working as a model in a New York department store. At that time, stores paid young women to twirl in designer dresses to showcase fashions to wealthy clients. My mother tried unsuccessfully to get that job, until the day she was lucky enough to apply right when another model who was her size quit at a moment’s notice. The gowns all fit my mother. The previous model left suddenly because she’d been discovered by Hollywood. Her name: Lucille Ball.

Despite that stroke of fortune, my mother knew that the most reliable avenue out of poverty was a good education. She was a stellar student with a photographic memory. Her grades earned her a full scholarship to New York University at age fifteen. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa at nineteen. Her college boyfriend was Herbert, outstanding scholar, student council president, and several years older than my mom. Herbert knew my mother was young, and he was patient with her hesitancy about having sex. My mom appreciated that sensitivity in him. After graduation, my mother married Herbert.

Once the United States got involved in World War II, my mother and Herbert moved to Washington DC to take jobs offered by their NYU economics professor. The professor entrusted my mom with a responsible position mediating national labor disputes, since the wartime emergency required unions and management to submit to binding arbitration. Mickey’s greatest coup was getting a higher wage for funeral home workers who prepared bodies for wakes, since they were underpaid compared to beauty parlor employees who did similar work.

Those jobs were an amazing turn of events for my mother and Herbert, children of the Great Depression. They mostly stayed in Washington DC when they held those positions. Neither of them owned a car, and in any case, my mother was a New Yorker who never learned to drive. One Sunday afternoon another couple took them on a drive through rural Virginia. It was spring, and it must have been an exhilarating experience to be young, gainfully employed, and feeling as if the world belonged to them.

The group stopped in a little country town and pulled up to the general store to buy snacks. On the storefront they saw a handwritten sign: NO DOGS OR JEWS ALLOWED. The four of them immediately got into the car and motored back to DC. It was a shock to my mother and Herbert that only a half day’s drive from the Capitol, they stumbled on an America that did not consider them Americans; would never consider them Americans. Even twenty-five years later, when my mother recounted this incident, she recalled it in detail. We don’t forget those slap-in-the-face insults.

My mother’s marriage to Herbert didn’t work out. Herbert was highly intelligent and sweet, but he and my mom both had a tendency toward deep melancholy, and they intensified that side of each other. Depression is like looking through Depression glass: it adds color, flame, and translucency to everything, but that color filters out much of the light.

A very odd thing occurred in my mom’s life following World War II. Not only did she and Herbert break up; another couple they’d known in their teens also split: my dad and his girlfriend, a nightclub singer named Sugar. When my father got out of the U.S. Navy at the end of World War II, he and my mom started dating. My dad’s former girlfriend Sugar then got together with Herbert, my mom’s ex. Both couples got married, and Sugar and Herbert remained some of our family’s closest friends. Growing up, I had no idea the couples had switched partners.

My dad, Lee Rogow, was a widely published writer and a drama critic in New York. He and my mom attended all the opening nights of Broadway plays. They also went out dancing in Manhattan, my mom dressed in her Christian Dior pleated black skirt and cuffed white shirtwaist. The two of them would rhumba to live bands at the Copacabana nightclub, winning contests for their smooth steps. This was a heady lifestyle for my dad and mom, whose parents still vividly recalled immigrating to the United States not many years before. Tragically, my dad died in an airplane crash when I was only three and my sister was five, in 1955.

My dad wrote a short story he never published about a man who was married to a woman who could “shatter into a jillion pieces” if she didn’t have a partner to help her through her lowest moments. But shattering is more or less what happened to my mom after my father’s death in 1955.

My mother felt she could not raise two children on her own, and any relatives equal to the task were already having difficulty providing for their own family. One night, not long after my father’s death, she dragged three mattresses into the kitchen of our apartment in Manhattan, shut all the windows, and stuffed cloths in the cracks. She put me and my sister to sleep on the mattresses and turned on the gas of the oven without lighting it. Then she lay down next to us.

Luckily, before any damage could be done, she jumped up, turned off the oven, and threw open the windows. My sister and I were too young to understand what had happened, and we both completely forgot the incident. I didn’t learn of it till many years later, when my mother confessed to me all that she’d almost done that evening.

And then something unpredictable happened. Faced with the responsibility of raising two small children as a single parent in the conformist 1950s, my mother rallied. She pieced her life back together after that initial failure of nerves. In so many ways, she turned out to be a wonderful mother—fun, warm, physically affectionate, enormously proud of me and my sister, and full of praise for everything we did. It astounds me how much courage it took for her to bring up two children as a single mom in those days when families that did not fit the mold were erased or looked down on. And she did that despite the dejection she fought off every day.

Mickey, Zack, and Maggie, 1959

My mom accomplished this partly by teaching me and my sister to enjoy what she enjoyed. My mom loved musicals, and we had a library at home of vinyl records of original Broadway show scores. Mickey was a smooth and sexy partner for a cha-cha or a mambo. She taught me and my sister the joys of social dancing.

The author and sister Maggie dancing, 1967

Our mom also had such a boisterous laugh that we sometimes got invited to the recordings of live comedy albums. The producers would put my mother in the front row so her guffaws registered on the record.

Having grown up poor, my mom adored speeding around Manhattan in taxis, smoking unfiltered cigarettes, and debating politics with cab drivers.

Not having had much parental support in her childhood, my mother keenly understood how important it was to applaud her children when they did well. When I was fourteen, I passed the competitive exam to gain admission to Bronx Science, then New York City’s most competitive public school. To celebrate my admission, my mom took me to dinner at a restaurant called Nirvana with a penthouse view over Central Park, treated me to a banana split at Rumpelmayer’s with its décor of giant teddy bears, and lastly piled me into a horse-drawn carriage for a ride through the park. I haven’t been on a horse-drawn carriage ride since that night—it just couldn’t measure up.

My mother loved carrying herself as a beautiful, fashionable woman, and receiving admiring attention. She liked to dress up in her sable coat, high heels that matched her outfit, and a discreet amount of jewelry. As femme as my mom could be at times, she also liked to wear men’s clothes. Mickey looked great in a man’s tailored white dress shirt, with a denim jacket, slacks, and a jaunty captain’s hat.

My mom had a 14-karat charm bracelet with a whistle she used to call New York taxis, standing out on an avenue in the rain as fearless as a hotel doorman.

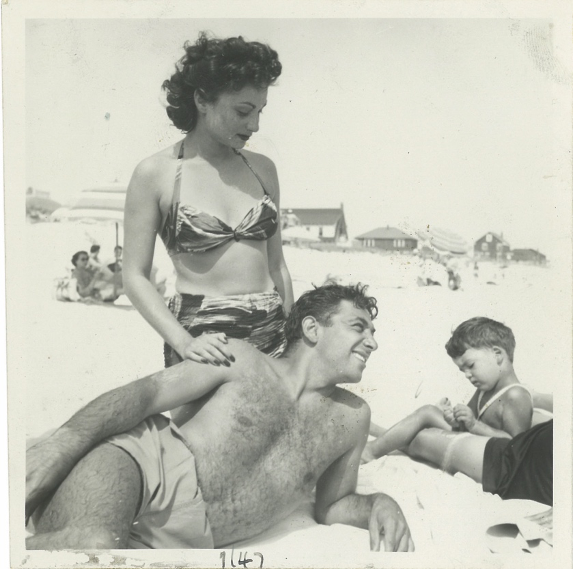

Widowed at age 36, Mickey was an attractive woman, the first to wear a bikini on Fire Island, a bathing suit she designed herself.

Mickey Rogow in the first Fire Island bikini

My mom had no shortage of boyfriends. They included the writer Ira Levin, author of Rosemary’s Baby, The Stepford Wives, and The Boys from Brazil. The dashing Ira was a scandalous ten years younger than my mom. Ira proposed to her, but my mother wanted a man who would also be good with my sister and me, and Ira seemed too young to fit that bill. Or maybe she just preferred her freedom.

Mickey Rogow with Ira Levin, 1957

One freedom my mother greatly appreciated was travel. From the time I turned twelve she took us every summer on another adventure. She passed on to me her love of other cultures and languages.

In 1966, when I was fourteen years old, she took me and my sister to the isle of Capri in Italy. Knowing the seas could be rough on the Bay of Naples, she arranged for us to arrive on Capri by helicopter. As we neared the island, it seemed to surge out of the sapphire water like a special effect from a movie.

On Capri, we passed an extremely elegant restaurant. My mother insisted on going in to look at the menu. She was entranced by the extravagant designer outfits of the women, adorned like exotic birds, with clothes right out of fashion magazines.

My mom announced, “We’re coming back to this restaurant tomorrow night, and I’m wearing my pajamas.” The following evening my mom dressed in her long, flowing 1960s pajamas with multicolored print fabrics. When we entered the upscale restaurant, no one blinked an eye. That night, the three of us giggled at our mom’s chutzpah, from the appetizers clear through to the dessert.

In 1967, when I was fifteen, I was incredibly curious about the new nonconformists called hippies. Centered in San Francisco, the hippies were living in communes, sharing private property, and experimenting with free love. I convinced my mom to take us to San Francisco for the Summer of Love so we could experience the hippies up close.

We rented a one-bedroom apartment in North Beach. When we went to the Fillmore Auditorium and heard psychedelic bands like the Grateful Dead and saw the rainbow-colored amoeba blobs throbbing on the walls, we were some of the few people there not tripping on acid. I must have been the only person who went to the Summer of Love with his mother.

My mom was a free spirit, but also compassionate. When we stayed at a Club Med on the Black Sea in Romania in 1968, my mother saw how poor the woman was who made the beds and vacuumed our room. When we took a side trip to Turkey for a couple of days, my mother asked the chambermaid what she wanted her to bring back, and the woman replied “slippers,” scarce under communism in Romania. My mom compared shoe sizes with the. maid, and when we were in Istanbul, she bought a fancy pair at the bazaar. I can still see the delight on that maid’s face when we got back to Romania and my mother presented her with those fairy-tale gold slippers.

My mom was a great entertainer at our home in New York, and she engaged in heated political arguments with dinner guests about the Black Panthers or the bombing of North Vietnam as she sat on the carpet in the living room in her velour sweater. She stretched out her tapered legs in patterned black tights, always puffing on her Pall Malls.

Mickey, circa 1968

My mom also taught me to prize social justice and activism by taking me and my sister to picket outside the Woolworth’s because their lunch counters in the South were closed to Black customers. On Election Day, she brought us into the voting booth so we understood our civic duty.

By the time I turned ten and my sister was twelve, my mother could already foresee the day when she would be alone in the house. That year, my mom searched for a job for the first time since my dad died. She hadn’t worked outside the home for a decade and a half, but she bravely walked in the cold to the Manhattan office of the New York State Department of Labor and asked about available openings. She’d been trained as an economist, so she went to that desk.

The woman who interviewed my mother responded in a surprising way: “Would you like my job? I’m retiring.” My mother was hired to help unemployed economists find jobs. My mom got quite a lot of satisfaction out of helping others find work at the New York State Department of Labor. She sometimes came home and couldn’t wait to tell us about an economist who’d been out of work for a long time, placed in a job he or she didn’t expect to land. My mom knew what it meant to really need a paycheck.

Just when my mother started to enjoy her new vocation, things took another turn. On her way to a work event, my mom was a passenger in a car that had a head-on collision. The windshield smashed into a thousand pieces; she suffered numerous cuts and bruises. The injuries forced my mom to give up her job in order to recover. That loss of employment and purpose took a toll on her morale.

One characteristic of my mother’s emotional condition is that she was either the life of the party, or she was deepest blue. Today she would probably be diagnosed as bipolar.

Part of my mother’s depression was the deep family trauma she carried with her, like a scar no one can see. My mom often told me about her own mother, Tillie, whose house was attacked by Cossacks during a pogrom in Ukraine before the family emigrated to the United States. Tillie survived by hiding behind the stove, but she heard the heartbreaking cries of several of her siblings being murdered. My mom also remembered stories her father Saul had told her about traveling to North America in steerage, trapped in fetid quarters below water level for a more than a week. Saul sometimes went up on deck where the first-class passengers traveled, not to exercise and breathe fresh air, but to sing songs for the wealthy passengers in order to beg for coins.

For souls like my mother and her ex-husband Herbert, less resilient than others, the shocks of the immigrant experience continued to reverberate in their daily lives.

I didn’t realize that depression was shadowing Herbert, and that he could never shake it. In October 1965, Herbert checked into a hotel and took an overdose of sleeping pills, ending his life.

When my mother heard the news, she was terribly shaken, partly because she did love Herbert, despite their not having brought out the best in each other as a couple. But also because his suicide opened the door again to her own self-destructive thoughts.

I went through two fearful years after my sister left for college in 1968. I would lie in my bedroom waiting to hear if my mother had settled down for the night in her room across the hall. Some nights I heard her crying, and I would rush in to find her in bed, with a bottle of Johnny Walker and a mostly empty glass on her bedside table.

My mother told me on those evenings that she could see her ghosts right there, above the bed, as in the Rodgers and Hart song she loved to hear Ella Fitzgerald sing, “Dancing on the Ceiling:”

I love my ceiling more

Since it is a dancing floor

Just for my love

My mom’s ghosts were her mother Tillie (who had died young of cancer), my father, and Herbert, and she couldn’t make them to go away.

I sat on the side of the bed and held my mom’s hand till she calmed down and was ready to sleep.

I left for college in the fall of 1970, unaware of what my mother would go through once she was alone again. Not long after I started my freshman year, one of my mother’s friends called to tell me that my mom had swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills. Fortunately the doorman of our building had found her when he tried to deliver a package and no one answered. My mom was rushed in an ambulance to a hospital, her stomach was pumped, and she was recovering.

My mother made another effort to restore her spirits after that attempt. She started seeing a psychotherapist and took a job as a writer and editor for the New York City Planning Commission. She got a great deal of satisfaction from her work, made new friends, went to parties. On one of my visits home from college, my mom brought home a man who might have been a boyfriend, and I saw him try to kiss her. My mom seemed like her old self.

But soon after, unbeknownst to me and my sister, my mother cut off the therapy and started to slide downhill again. Before we could arrive home for spring break from college in April 1972, my mother stepped out of the window of our apartment on the seventeenth floor, and took her own life.

On the day she died, I removed my glasses and refused to wear them, even though I’m very nearsighted. I didn’t want to see a world where my mother could have such a fate. That same night, I had a strange dream that I was holding tight to a pillow and flying around New York, rollercoasting up and down the avenues, above all the crowds and the taxis. Oddly, it was a feeling of release, as if I was no longer being pulled down by gravity.

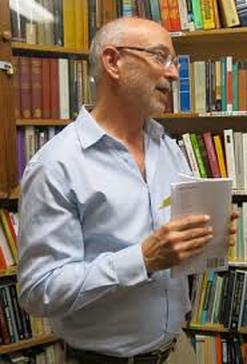

Zack Rogow is an American poet, playwright, translator, and critic. He was born in New York City, and currently resides in Berkeley, California.Rogow is the author of nine books of poetry, including Irreverent Litanies,”from Regal House Publishing; and Talking with the Radio: poems inspired by jazz and popular music and My Mother and the Ceiling Dance, both published by Kattywompus Press; and The Number Before Infinity, published by Scarlet Tanager Books. His translations from the French include works by George Sand, André Breton, Colette, and Marcel Pagnol. His co-translation of Earthlight by André Breton received the 1994 PEN Translation Prize. His sequence of short poems, Airplane Tanka, was a cowinner of the 2006 Tanka Splendor Award.

The anthologies that Rogow has edited include The Face of Poetry, a selection of work by contemporary U.S. poets with photos of the writers by Margaretta K. Mitchell, published by University of California Press. He also edited two volumes of the journal TWO LINES.

He has written four plays in a series about contemporary world writers. The fourth in this series, Colette Uncensored, a one-woman show about the French writer Colette, was co-authored by actress, Lorri Holt. Holt played the part of Colette when the play had its first staged reading at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC in February 2015, and again when the play ran at The Marsh in San Francisco and Berkeley, California, in 2016 and 2017, and in London at the Canal Café Theatre in 2018. The other plays in the series concern the life and work of Léopold Sédar Senghor, Nâzım Hikmet, and Yosano Akiko.

Rogow co-founded the Lunch Poems Reading Series at University of California, Berkeley with Professor Robert Hass and is a contributing editor of Catamaran Literary Reader.