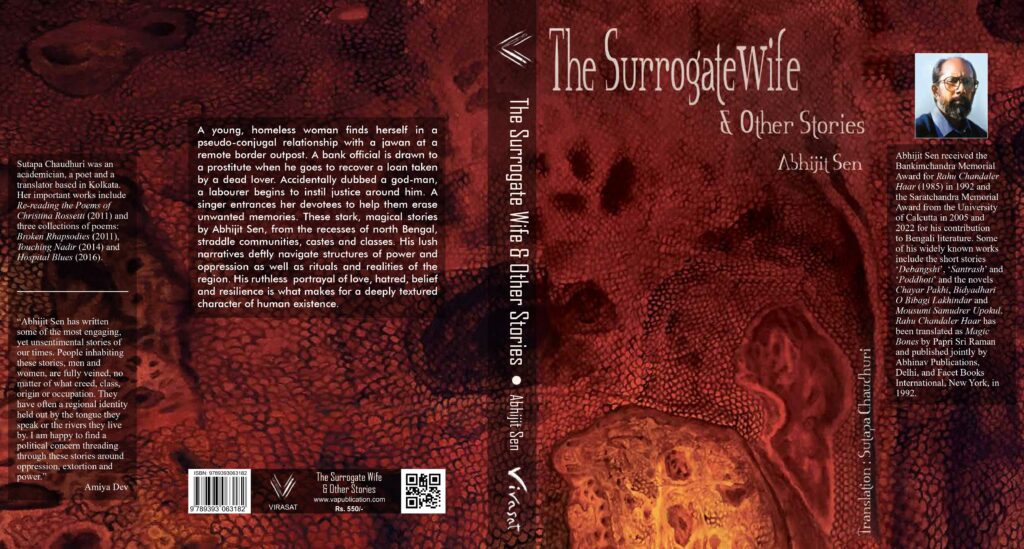

From the short story collection The Surrogate Wife and Other Stories, trans. Sutapa Chaudhuri, VIRASAT ART PUBLICATION, Dec. 2022. Cover artwork by art collective Le braccianti di Euripide.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon. The prostitute quarters on the canal bank were abuzz with activity. Nikhil got down from his rickshaw. He had been feeling uneasy, coming to this neighbourhood riding on a rickshaw. To do away with that uneasiness, after a while, he began to chat with the rickshaw puller, needlessly explaining to him how difficult it was to work in a bank. And how, as a consequence of that, the manager of the bank too had to visit a red-light area sometimes on official errands. But the irony of the situation was that Nikhil was forced to come to perform his duty in a place that treated all men—boys, young men, old men—as cherished visitors! And what duty was that? He had helped someone one day, and that assistance had now become a burden pressing tight on his shoulders.

There was really no reason to feel so embarrassed. For the rickshaw puller knew very well who he was; and surely, he also knew the men who regularly visited this area or came to the canal-side road on a rickshaw. Thus, there was no need to explain to him that Nikhil was not going there for a tryst. Actually, Nikhil felt uneasy because of the dirty looks given by the bystanders.

Moreover, he would require the help of the rickshaw puller in finding out the address he required. And that was another reason for which he had began to chat with the rickshaw puller all of a sudden.

The name of the man who pulled the rickshaw was Sushil. He was middle-aged. He said, ‘What would you get there, Manager Babu? I believe it would be entirely fruitless for you to go there.’

Nikhil said, ‘Arrey, no, I’m not going there to get anything. I just need a signature from Mohan’s wife on my papers. If I can get it, that will be enough for now.’

He did not have the guts to reveal anything more. For the rick- shaw he had been riding so long was hypothecated to the bank too. Though Sushil was more or less regular in paying off his debt, if he got to know too many loopholes in the law, he too might act smart. Then the bank would run at a loss.

‘Would you file a case against her, Manager Babu?’

Nikhil could not decide then and there whether he should tell the truth or, perhaps, keep his profession’s profit in mind.

After a few moments he replied, hesitantly, ‘Why, what if we file a case? A case can surely be filed.’

These words could have two meanings. Sushil took the second meaning. He replied, ‘Can you get the loan repaid, even if you file a case against her? From where would she ever bring out the money, and why would Shefali even take the burden?’

Nikhil thought that perhaps Sushil was trying to understand the nitty-gritty of loan repayments. He tried to cosy up to Sushil in a different way to divert him from the track. He said, ‘With all of you around, how could the woman land up here of all places!’

Sushil was wearing a string of tulsi beads around his neck. He looked away and said softly, almost to himself, ‘Yes, we were all around!’ The string of beads on his neck became taut. He stopped a sigh midway. The whole process got caught in Nikhil’s eyes. At this he became somewhat perturbed. Sushil had smiled wanly then. He said, ‘Can you tell me, who thinks of others at all these days?’

Inside the run-down hovels on the canal-side road, the residents were busy with their afternoon cooking and eating. Who didn’t know that in these areas morning dawned much late?

Sushil approached an old woman and asked, ‘Burima, can you show us Shefali’s room?’

The old woman snapped shrilly, ‘Which Shefali do you want?’

‘Shefali, Mohan’s wife—’

‘The fair Shefali or the dark one?’

‘Arrey! Mohan’s wife, that very Mohan who was murdered last year, that Mohan who used to pull a rickshaw, don’t you remember anything at all?’

‘Ah, then it’s the fair Shefali after all.’

‘Yes, which one is her room then?’

A little girl pointed to a hovel nearby and said, ‘There is Shefali Aunty’s room.’

Nikhil went with Sushil towards Shefali’s room. A small, newly thatched hovel. The bamboo-lattice on the door too was sturdy. By the side of the larger room, there was a smaller low-roofed structure sharing the same wall. A woman sat there, busy cooking, with her back turned towards the door.

The little girl had accompanied Nikhil and Sushil. She called out loudly as they approached, ‘Shefali Aunty, they are asking for you.’ The woman turned her face from where she sat.

Nikhil had first seen this woman four years ago. At that time a new branch of their bank was opened in the suburbs. Very few people worked in that office then. Nikhil had been posted there as the manager. It was during those first few days that Mohan had been granted a loan from the bank for buying a cycle-rickshaw.

Mohan never paid the monthly instalments. At that time, there was not much work in the bank. Nikhil himself sometimes went out to knock on the defaulters or collect the instalments. One day he saw a very drunk Mohan misbehaving with the passengers near the rickshaw stand; the day after, he went to Mohan’s place. He was afraid that the loan may not be realized at all.

Mohan was not at home. His wife Shefali was trying her best to split a piece of hard wood. Her anchal was wrapped tightly around her waist. On her half- exposed back, droplets of sweat had accumulated. The hint of a well-rounded breast did not escape Nikhil’s eyes.

Nikhil was not at all a depraved man. But yet, for a few moments, he had ogled at the young woman without calling out to anyone or making his presence known. Nikhil had stolen those

few moments, just so far as someone as polite as him could afford. Then he had cleared his throat and said, ‘Isn’t Mohan home?’

Startled, Shefali had looked back—hurriedly dropping the axe from her hand and covering her exposed body. The gaze of a fascinated man was more embarrassing for a woman than the ogle of a brazen man. For, this incident often brought in many unusual reactions and extraordinary consequences. When the reaction was normal, that captivation would lead the two people towards an ordinary outcome—it was a different matter whether that outcome proved good or bad finally. But as a result of abnormal reactions, it sometimes happened that the man and the woman would continue to afflict and deceive each other for a long time, indeed even for their whole lives. It so happened that sometimes none of them realized the processes of this affliction and deception, or maybe, at other times one of them understood, the other did not. If they both understood, then the game between the two became extremely interesting. They would help create an extraordinary moment around them woven with sweetness and despair. It was a strange game, as it were. Although there were a few conditions in this exercise, there were no rules, whatsoever. The main condition here was the presence of an insurmountable boundary between the two. If one among the two ever crossed the limit, even by mistake, it could be understood that he or she had been mistaken from the very beginning. He had not come to play the game at all. The match he had been playing was merely that of ordinary relationship traditionally at play between a man and a woman. An apparently unrealistic, but indeed, extremely realistic subject such as this was more than possible between a man and a woman.

As a result of such thoughts, Nikhil had frequented Mohan’s house a few more times after the first visit, with the same excuse, namely, to collect the payment for the loan. Shefali too had visited the bank branch either to deposit the instalment for the re-payment of the loan or merely to carry on with the same excuse.

Shefali was quite sprightly and at ease, despite her social position. Nikhil could understand that clearly right from the first day.

‘No, he’s not home. May I know who you are—?’

‘I’m the manager of the bank. He had taken a loan to buy a rickshaw, hadn’t he? I’m here regarding that—’

By then Shefali had measured the depth of the captivation in Nikhil’s eyes and, placed a stool in front of him to sit upon, but only after wiping it thoroughly with her anchal.

Nikhil had sat on it. Spoke a few words, imparted some bits of advice, discussed one or two things, albeit those were all about the loan and its repayment. Finally, Shefali too had pitched in.

And at the time of leaving, Nikhil thought that he had come only to deliver a few threats, perhaps even to make her a little afraid of the law.

Three years had passed after that. Every two or four months, Shefali visited the bank to deposit twenty or twenty-five rupees as part payment for the loan Mohan had taken to buy his rick-shaw. Every time she had made it a point to sit on a chair facing Nikhil and because it was a small-town branch of a bank, no one had seen anything to censure here. Nikhil had asked, ‘How are you Shefali?’ In reply Shefali had only smiled a little. Gradually, in this manner, as an answer to those words, she too had ventured far enough—she had even gathered the courage to ask ‘How are you’ in return.

A few words like these, apparently very ordinary, a feeling of fascination, and of envy— and to top it all, a sense of an insurmountable boundary that could never be crossed. The impossibility of stepping over was an unquestionable dictate to both of them—and so three years passed in this manner.

Sometimes a selfish thought—that a woman like Shefali had to live in such a place or was married to a rickshaw puller like Mohan—had lacerated Nikhil’s heart with despair. But, when

Shefali, wearing a cheap but new saree, had sat on the chair in front of him and said, ‘How are you, Manager Babu?’ in her soft and sincere voice, it had instantly made all discussions of loans and repayments meaningless and futile.

Thus, not even half of Mohan’s loan got repaid. Nikhil too had not been bothered with it much. For as long as the loan remained, there would be a possibility of seeing Shefali, albeit within and

respecting the invisible, but sacred, boundary. This possibility itself touched his heart lightly as though with a sweet ache.

Thereafter Shefali’s visitations had become more and more irregular. And Nikhil had, time and again, seen Mohan engaged in numerous drunken brawls on the open road. In all these flux, the words, ‘How are you, Shefali?’ had become laden with much more significance and touched them both. Finally, in some brawl or other, Mohan was murdered, just as it had happened time and again in this town. At this a thought had merely crossed Nikhil’s mind just once, as was his professional habit, that the loan would now become ‘sticky’. But, in spite of it, he had not felt sad for Shefali’s misfortune.

Thereafter, Shefali had not come to visit and he too had not gone to meet her. As he saw Shefali after so many years, he felt that despairing ache and envy rise within him. Nikhil could see clearly that smoke was rising from the kadhai on the stove, and in front of it sat Shefali, busy cooking, her back turned towards the door. And on her uncovered back were droplets of sweat, just like that very first day. Nikhil stood a few feet away and waited.

Hearing the little girl call out to her, Shefali turned her head back, and instantly her face crumpled—just as people break down when struck by a sudden disaster or an unwanted surprise.

Her whole face seemed to be breaking down to bits. The mixed emotion of distrust and fear crept into her eyes and veiled them quickly. In an instant she turned her face away and hid it between her two knees. And the next moment she got up and hastily went inside the room.

Nikhil was astounded; he did not know what to do. Unprepared, he stood there speechless. The folio in his hands sweated. Then he heard a faint whimper from inside the room. It was Shefali’s.

But that was only for a little while. Shefali controlled herself and brought out a chair from inside the room. She placed that chair so that it was visible directly from the door and said,

‘Please come inside, Manager Babu.’

Nikhil became even more uneasy. For a moment he could not understand what he should do. He glanced at Sushil. A little farther away, Sushil sat on his rickshaw. He was looking this way.

As Nikhil tried to make eye-contact with him, he turned his gaze away. As a result, Nikhil shrugged off his discomfort, stepped inside and sat down on the chair. Inside the room was a bed. Shefali sat there. Her face was turned sideways. The room was furnished in an ordinary manner.

A calendar hung on the wall, there were a few framed photos, and a new transistor stood on a small wooden cupboard.

For a long time, there was an awkward silence inside the room that, after a while, felt almost suffocating. Then Nikhil said, ‘How are you, Shefali?’ Nikhil’s words seemed to pierce her instantly with a terrible pain, a sensation for which she was not prepared even a moment ago. Shefali turned her bowed head slightly. Nikhil observed that she had become more beautiful, something that he had never expected. Till now he could see no sign or mark of her profession on her face. This amazed Nikhil further. Shefali smiled a little. Her eyes were heavy and clear. She said as before, ‘How are you, Manager Babu?’

Nikhil looked at her more closely. Shefali lived well, he could easily figure that out. At least she could get decent food and clothing. Her pretty face and attractive body must have helped her in her profession. For she seemed to be quite well off now. Nikhil mulled over all these in his mind and gradually regained his customary confidence once more.

‘I’m going away from here, Shefali.’

Shefali raised her eyes once again. Her heavy eyes brightened suddenly. As though she had suddenly got something worthwhile, some very valuable gift, perhaps something she did not deserve.

‘And so, you’ve come to bid goodbye? To see me for the last time. But why did you come here, Manager Babu?’

She hid her face in her anchal and whimpered, choking with emotion.

Nikhil sat there thunderstruck. The ease that he had been feeling a few moments ago left him. He realized that he had himself crossed the limit, although unconsciously—the sacred barrier that existed between them. But Shefali was still firm in her own position, trustful and believing. And yet, this woman worked as a prostitute!

Nikhil needed time to compose himself. He would have to compose himself, for he had tried to placate himself by saying that, he had no other way out, had he? After a long while, and after much ado he had been finally transferred to a branch near his home. The man who would take charge here had arrived already. But by the rules of the bank, whatever loopholes there were in old paperwork, had to be made good by the old cronies themselves. The old loans that were now time-barred had to be renewed. That is, the legal documents had to be prepared again, otherwise the new officers would not take any responsibility for them. Gradually, Nikhil became more unkind. Legally, Mohan’s heir was Shefali, who else! Thus, it was she who will have to sign on the renewal papers.

Nikhil said, ‘Yes, you had not pursued it any further, had you? A few legal hassles remained. Before leaving this place, I would like to put an end to all of it. Who is pulling Mohan’s rickshaw now?

Shefali slowly raised her head. On her eyes were disbelief and fear. She looked straight at Nikhil’s eyes. Nikhil lowered his eyes.

Shefali answered, ‘The rickshaw was sold off and the money had to be used for performing his last rites.’

Now Nikhil turned his gaze outside the door. Nevertheless, he said, ‘Yes, that is quite alright. It had to be done. But, you know, the trouble is that, the loan from the bank too remains on yourshoulders.’

‘On my shoulders!’

Shefali even forgot to look surprised.

‘Well, legally of course. That is, I’m not asking you to repay the loaned amount right now. Just, you need to sign in three or four places on my papers.

Shefali tucked her chin between her two knees and remained motionless. An heir! After all, what did the word mean! There were so many answers to these terms. And more so, especially for the person sitting in front of her. Still, it was unbelievable how everything could be broken and shattered at one blow like this!

Nikhil felt that all his masks were falling apart, all over his body and even inside his bone marrow. But he was trying so hard to hide everything from the other’s eyes. He truly understood

now what he had been doing consciously. If he stayed there for some more time, he would go blind, he might go deaf too.

He unzipped his bag and brought out the papers. Three revenue stamps were stuck on three papers. The papers were reddish in colour, with a legal look. Leaving the chair, Nikhil took out a pen and advanced towards the bed. He said, ‘Please put your signature on these three places. Then, afterwards, it will be well if you can pay, if not then—we’ll get much time to think about that later.’

Raising her face from her knees, Shefali said, ‘And if I don’t sign, then?’

She smiled wanly, full of meaning. Nikhil wanted to cover up his eyes. He well understood that he was gradually getting exposed. Shefali’s youthful, pretty face was very near him now. If the bank ever wanted to file cases against these small unpaid debts, then this sheaf of signed papers would be used as evidence at the court. If there was no signature then it would be difficult to go for lawsuits. It would be more difficult for him too to leave this branch. He became angry suddenly. And moved aside, away from Shefali. He said curtly, ‘It is up to you to sign or not. I can’t force you, can I?’

He put the files back into his bag once again and realized right away that this too was merely a ploy of his. He had to get the papers signed. He felt that Shefali was tormenting him cruelly and possibly with some ulterior motive. She must have had a design all along, a minutely detailed plan behind it all.

‘How much money still remains unpaid, Manager Babu?’ Shefali enquired.

Nikhil answered, ‘A little more than five hundred rupees perhaps.’

Shefali said, ‘You return to your office today. Tomorrow I’ll send the money by someone.’

Nikhil lost his control. He turned swiftly to glance at Shefali’s face, taken aback.

Shefali said, ‘Then I don’t have to sign anywhere anymore, right?’

Nikhil seethed inside. There was no doubt that Shefali would pay the money back. He replied shortly, ‘Well, goodbye then.’

He knew that the game between the two of them was over now.

He too felt like a broken man. He did not look back, not even to ee whether Shefali had broken down in tears.